As I sit down to write, a Willy Wagtail bobs and flashes outside the window, chirping and warbling across the trees in the garden. I am reminded of the interview that I did with Maxine Mackay in Bourke, where she told me of her mother’s connection to the Willy Wagtail; how she knew its temperament, and how she would carefully listen for what it had to say, always heeding whatever the little bird would tell her. It’s not the sort of conversation you have everyday (not in my world anyway) but while working on this project I have had that conversation many times. I have been engaged with tales of spirit animals, sacred lines in the earth, traditional knowledge, lost language and deep mysteries. I have had the sensation of stepping behind a molecule and into a parallel world, entirely overlaying the world that I have always lived in – a world of culture, knowledge and connection.

The project, Living Arts and Culture, is an initiative of Outback Arts, the Regional Arts body covering the Local Government Areas of Bourke, Brewarrina, Cobar, Coonamble, Nyngan (Bogan Shire), Walgett (including Lightning Ridge) and Warren. A remote and sparsely populated part of Western NSW, with a high population of Aboriginal people, both from the region and from elsewhere in the country. Within this area there are approximately 25 language groups represented by small and large family groups. Following traditionally recognised ‘boundaries’, the land is that of the Murrawarri, Yuwaalaraay Gamilaraay, Barkinji and Ngemba, and the various associated clan groups. Within these communities, there are Aboriginal artists working with differing levels of support and tutelage. This project was initiated to develop professional profiles for the working artists to consistently present and describe themselves and their work to a wider audience.

The way we approached the project was a bit like a snowball – or a pyramid marketing scheme – start off small with what we knew, and build it as we went. The original list of artists was impressive, though not comprehensive, and every time I would talk to an artist, I would ask who else they knew that was working in the cultural space. This led to a very long list of individuals, some with contact details, some with vague directions and arm waving gestures. The ‘list’ at the conclusion of the project was roughly four times as long, and it still isn’t final. Growing and changing as people move, become engaged or fade away. The project is called ‘Living Arts and Culture’; after all, there’s no real way that you could ever get to the end, or even define the start of a project like this. You just get a little snapshot of whatever you can within the time you have to work with.

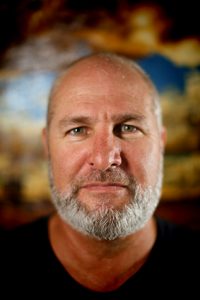

In addition to enhancing the database, I had four basic questions that I used to underpin each interview: “Who are you and where do you live?”; “What is your tribal or language lineage?”; “What is your practice and when did it become important to you?”; “What does the future look like?” – Some of those are double-barreled questions but the idea was just to have a consistent frame for a conversation, something we could use to relate an established artist working in Cobar, like Sharron Ohlsen, to an emerging artist working in Warren, like Lila Gordon. The other thing I imposed on the subjects, was the need to sit for a photographic portrait. Again, these portraits were designed to be thematically consistent: full face, looking into the camera, with shallow depth of field.

The result is this exhibition and publication, along with the associated database, website, contact information, etc. With these products, Aboriginal artists in the region will have tools they can use to promote their work, and Outback Arts can adopt a region-wide approach to informing the world of what can be found within this part of Western NSW. What can’t be presented, photographed, written down or exhibited, is the cultural story that is deep in the psyche of all project subjects.

This is the part where we listen to what the Willy Wagtail has to say, where we know we are welcome by the nod of the Emu, and where we the marks that are etched into the earth are familiar and meaningful in a way that cannot be written down. The element that really linked all the people in this project was not the same questions they were asked, or the same way that they were photographed. It was the way that, in every case, it was vitally important to each individual that they pass on their knowledge. Even in acknowledging that they needed to know more, the people of this project invariably wanted to be a conduit for knowledge and connection for the younger generation.

In many cases, as you might expect, the story of the people is tinged by loss, and disenfranchisement. While there is no where near the space to properly convey that story here, suffice to say, the sadness and sense of loss can be overwhelming and all consuming. Many of the artists now work in ways that represent traditional forms but are overlayed with contemporary styles and techniques. They have had to invent a way of understanding and interpreting their world and their particular situation. The people represented in this project all know that. They know that the story and information they have to work with comes from various sources, but there is a clear sense of wanting to own and create that narrative, to understand it, to build on what they have, and convey it clearly, so that it never gets lost again. That need to convey understanding has given me new eyes.

With my new eyes, I can see in a nightscape photograph by George Williams, a meaningful conversation with the Emu in the Sky, while he waits for the long exposing shutter to click. I can understand that the process of weaving that Kristy Kennedy still uses in Bourke, links her to her past, her future and her very soul, all of which is tied to every object she makes. I can glean that making traditional tools and weapons, for Tom Barker, is more about walking in the bush looking for the right bend in the right tree than it is about crafting wood. I can see that I need to listen more to the Willy Wagtail, amongst other things.

I commend to you the portraits of all these people and a tiny snapshot of their stories, and in doing so, I urge you to look further, connect more deeply, and stay engaged with them and their work. It is work that describes the past, present and future of this region, and is made by the people who can and will change those things.